She lifts her suitcase and it rattles loud as popcorn in a microwave oven. The sleeves of her sweater lumpy with dirty tissues stuffed inside. Saint Gut-Free pulls the lever to fold open the door, and standing on the curb is little Miss Sneezy. Whittier sitting near the front with Mrs. At street corners or bus-stop benches, until Saint Gut-Free drove up. A purse handmade to lug around the Word of God.Īll over the city, we waited for the bus. Sister Vigilante, she brought a fake-leather case with a strap handle, a flap that closed with a snap to protect the Bible inside. That was the day we missed our last sunrise.Īt the next dark street corner, where Sister Vigilante stands waiting, she holds up her thick black wristwatch, saying, “We agreed on four-thirty-five.” She taps the watch face with her other hand, saying, “It is now four-thirty-nine. Clark, her breasts so big they almost rest in her lap.Įyeing them, Comrade Snarky leans into the gray flannel sleeve of the Earl of Slander. Whittier, where his spotted, trembling hands can grip the folded chrome frame of his wheelchair. Women either lift or tint the color of their hair.” Sitting next to Comrade Snarky, the Earl of Slander was writing something in a pocket notepad, his eyes flicking between her and his pen.Īnd, leaning over sideways to look, Comrade Snarky says, “My eyes are green, not brown, and my hair is naturally this color auburn.” She watches as he writes green, then says, “And I have a little red rose tattooed on my butt cheek.” Her eyes settle on the silver tape recorder peeking out of his shirt pocket, the little-mesh microphone of it, and she says, “Don't write dyed hair. Sneaking out on tiptoe with our suitcase down dark stairs, then along dark streets with only garbage trucks for company. With one suitcase still on the curb, abandoned, orphaned, alone, Comrade Snarky sits down and says, “Okay.” Comrade Snarky tucks the luggage tag in her olive-green pocket, then lifts the second suitcase and steps up into the bus. ,” Saint Gut-Free says into the microphone that hangs above his steering wheel.Īnd Comrade Snarky says, “Fine.” She leans down to unbuckle a luggage tag off one suitcase. With a black beret pulled down tight on her head, she could be anyone. When the bus pulls to the corner where Comrade Snarky had agreed to wait, she stands there in an army-surplus flak jacket-dark olive-green-and baggy camouflage pants, the cuffs rolled up to show infantry boots.

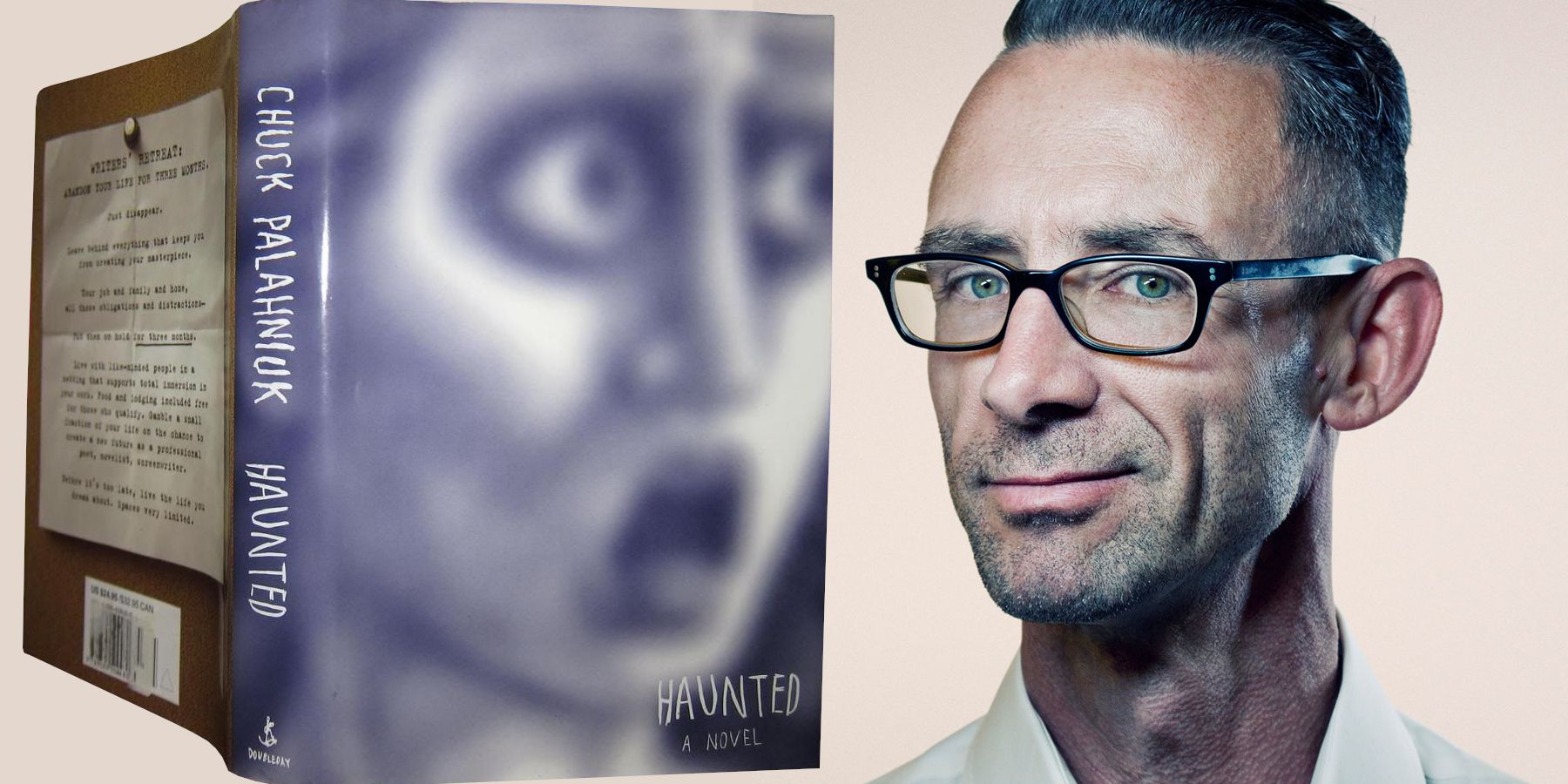

No, this was only a writers' retreat until it was too late for us to be anything,

It doesn't matter who we were as people, not to old Mr. Spring, summer, winter, autumn-one whole season of that year. Too many of us, locked away from the world for one whole A lot of hot, sticky blood.Īnd we were supposed to write short stories. Real intestines, real lungs, a beating heart, blood. As if you cut open a rag doll and found inside: Names based on our sins instead of our jobs:īased on our faults and crimes. The names we earned, based on our stories. You called peonies-sticky with nectar and crawling withĪnts-the “ant flower.” You called collies: Lassie Dogs.īut even now, the same way you still call someone “that man with one leg.” The same way-when you were little-you invented names for the plants andĪnimals in your world. Locked away from the ordinary world for three months.Īnd we called each other the “Matchmaker.” And the “Missing Link.” Run by an old, old, dying man named Whittier,Īnd we were supposed to write poetry. It was supposed to be safe.Īn isolated writers' colony, where we could work, This was supposed to be a writers' retreat. There was much of the beautiful, much of the wanton, much of the bizarre, something of the terrible, and not a little of that which might have excited disgust.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)